Simple and stylish, an open-riser staircase will add a note of distinction to your home. With the right techniques you can build yourself an attractive and streamlined staircase. The building of a glass and metal open-riser staircase is a major construction job which has to be carried out accurately to achieve a good result, as well as to conform to any building regulations that apply in your case.

It is a long and heavy job, and you may need assistance at certain stages. There are two basic designs for open-risers. The most common one is where the steps, or treads, are supported at their ends by strings, timber pieces that run the whole length of the staircase. Housings are cut into the strings to accommodate the treads. In the second design the treads are supported from underneath by means of long timber pieces called spines. For either design a power saw is virtually a necessity and for the first design a power driven router, to cut the housings in the strings that take the ends of the treads, is a great advantage. An alternative method of cutting the housings is, however, given below. An electric orbital sander will considerably simplify the job of finishing the staircase. Hardwood is the ideal timber for the staircase, 250mm x 40mm being a size that will give solid construction.

Softwood can be used, but unless it is an unusually strong type such as parana pine or British Columbian pine, the size should be increased slightly. For example, if common redwood or whitewood is used, a size of is more suitable.

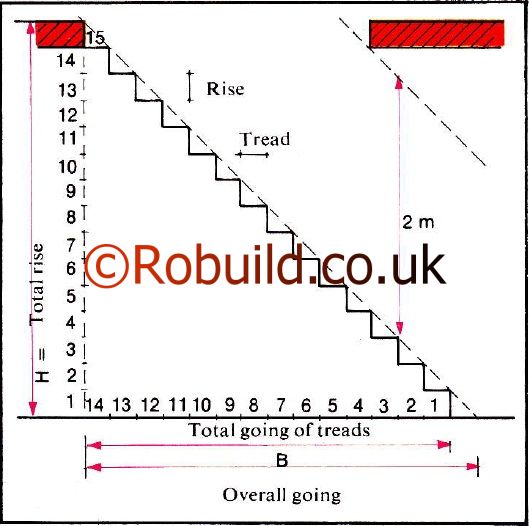

These sizes apply to strings or spines and treads alike, unless the treads are unusually wide. Technical terms You will need to understand a few technical terms when planning your staircase. Going is the horizontal distance between the front edge of one tread and the front edge of the next.

Rise is the vertical distance between the face on one tread and the face of the next. The pitch line is an imaginary line drawn through the top facing edge of each tread. This indicates the angle at which the staircase slopes. Construction requirements In Britain, all new constructions must conform to the requirements laid down in the Building Regulations. In the case of open risers, the requirements are complicated but the basic ones are that: each step must be level, all steps must be of a similar rise, the going of each step must be the same, each step must overlap the next, on a plan view, by 16mm.

In addition to these basic items there are more complex requirements. Sufficient headroom must be provided. Measured vertically from the pitch line, the clearance must be at least 2m to the ceiling. Measured at right angles to the pitch line, the clearance must be at least 1.5m to the ceiling. All staircases must be enclosed on both sides either by two walls or a wa1l on one side and a baluster on the other or balusters on both sides. A baluster or railing, this must be at least 840mm high, measured vertically from the pitch line. At landings the minimum height is 900mm.

In Britain, the Building Regulations also dictate the sizes of the rise and the going. There are two sets of regulations applying to private open-riser staircases, i.e. those in domestic use and ‘common’ open-risers those used in public buildings. Be sure to consult the correct set. For private open riser the minimum going is 220mm and the maximum rise is also 22Omm. In addition, your staircase must conform to a certain formula. The sum of the going of a step plus twice its rise should not be less than 550mm and not more than 700.

The pitch of the staircase will also dictate the rise and going you use. Private open risers must not have a pitch of more than 42′ to the horizontal. Therefore you cannot work to the maximum rise of 220mm and the minimum going of 220mn as this will give you too steep a pitch. It is illegal in Britain to have an open-riser staircase leading to an attic unless there is some alternative means of leaving the attic, such as an external fire escape. There is no simple formula for planning open-riser stairs.

Take all the considerations given above into account when making your dimensional drawing for presentation to your local planning officer. He will tell you whether or not your planned staircase meets all the requirements.

Measuring the stairway

If your open-riser is to replace an ordinary staircase you may be able to use the same dimensions for the new construction as were used for the old. For example, the rise of the old staircase may be suitable to allow you to position the new treads in the same place as the old. You cannot, of course, simply remove the riser from an ordinary staircase to give you an open-riser staircase. This would make the whole structure come loose and fall apart. If the dimensions do not conform, or the staircase is a new feature, then the first step is to measure the overall length of the stairway.

To do this, measure accurately the distance between the floors that the open-riser is to connect. You must make sure that you allow for any slope on the floor, or your height measurement will be out. Make a scaled and dimensioned drawing showing these two levels. Take the maximum permitted rise between one step and another and divide this into the overall rise-the distance between the two floor levels.

This will give you the minimum number of treads you can use. From this, you can calculate the minimum overall going of the staircase -the horizontal distance between one end of the staircase and the other. Once the overall rise and going have been calculated check that the headroom this construction will allow conforms to the regulations. To do this, first mark on the lower floor the position of the bottom of the planned staircase. From this point, to the edge of the upper floor level, stretch a length of string, fixed at the ends with nails. Measure the headroom from this string, both vertically from it and at right angles to it.

Use a steel tape rule to do this. ll the headroom is too tight, reduce the overall going if you can. If there is plenty of headroom, you may wish to increase the size of the treads or decrease the rise between each of them to, ideally, about l90mm. This will make the staircase easier to ascend and descend. Having made these calculations, check that they conform to the formula for private open-risers given earlier. For example, if the overall rise is 2.20m the number of rises will be ten, with an individual rise of 220mm. If the overall going is 2.50m this will give you ten goings at 250mm individual going. Twice the individual rise is 440mm. This, plus one individual going adds up to 690mm. This figure is more than 550mm and less than 700mm so this particular design conforms to the requirements. The final step in ensuring that the staircase conforms to the British Building Regulations is to check the pitch of the staircase. It must not exceed 42″.

You can do this simply by laying a chain-store protractor on your scale drawing. Design considerations There are two basic designs of open-riser staircases. In the first the ends of the treads are housed in channels cut in the strings, or long timber side supports. In the second the treads are supported from underneath by means of spines. Triangular blocks of wood are fixed to the top edge of the spines so that the treads are horizontal. The use of strings gives better fixing for the handrails and balusters-but this is not an insurmountable problem if you want spines. If you design your staircase with spines, you must use more than one spine.

If only one spine is used, the treads would create excessive leverage on the spine if you put your weight on one end of them.

Setting out the tread supports

In both types of staircase, the angles for making out the supports to show the positions of the treads have to be determined. This is done by using similar triangles. A similar triangle is one that has the same angles as another triangle but is larger or smaller than it. In this case, the distance between the treads is estimated by drawing a similar triangle to that formed by the planned pitch of the staircase, the floor and a vertical line to the floor from the upper floor (the one to which the staircase will run).

The two sides of the triangle that meet at right angles should be as long as the planned rise and going of the individual treads. Make a template, sometimes known as a pitch board in this context, to match these sizes. This can be cut from hardboard or plywood. If strings are used to support the treads the next step is to mark the distance you require between the top edge of the treads and the top of the strings. This distance is known as the margin. Mark it lightly with a marking gauge, or with a pencil and a strip of wood cut to the width of the margin.

Along this line mark off distances that equal the longest side of the triangular template you have cut. Then lay the template along the marked line between the stepped off points, with the longest side against the line. Draw a line on the string along the bottom edge of the template. This will indicate where the top edge of the tread will come. Then mark on the strings the cross-section of the treads. Use a piece of the material you intend to use for the treads as a template.

Mark out this section tight the timber will be cleaned up later and it is desirable that the treads should fit tightly into the strings. If spines are to be used to support the treads, step off the length of the longest side of the triangular template on the top edge of the spines. Do this with the planks laid together and their faces butting. Square lines through these marked points. This will indicate where the top edge of the triangular support blocks should meet the spines. The triangular template can also be used to mark the angle at which the support pieces, either strings or spines, meet the floor.

Lay the template on the pieces at the correct point with the longest side parallel to the top edge of the support piece. The side that indicates the going on the template gives the required angle for the line where the support piece meets the floor. The side that indicates the rise on the template gives the angle for a vertical end to the support pieces, for example for the mortise-and-tenon joint used where a string is inserted into a newel post.

Housing the treads in the strings

The next step, if the treads are to be supported by strings, is to cut the housing joints on the inside face of the strings. The housings should be a minimum of l3mm deep. You can cut them with a power router and a jig, if you have one, and it will save you a lot of time. If you do not have such a tool, you can cut the housings by drilling a series of holes within the areas marked out for the treads. These holes can be cut with an electric drill or a handbrace and bit. In either case it is advisable to use a depth stop to keep all the holes an even depth and avoid the necessity of having to even up the housings later.

A depth stop can be a piece of wood with a hole drilled in it that fits around the bit the required distance from the tip. Stop the wood from moving up the drill with a piece of adhesive tape. Alternatively, a proprietary type of stop that bolts onto the bit can be used.

Drill the holes so that their edges are almost touching. Remove the waste with a chisel and mallet. Carefully shape the front of the tread section to a rounded shape with the chisel; the fronts of the treads should be rounded off to save your shins. The treads can now be cut to length. Each tread should be fitted individually to a particular housing. Number the ends of each tread and each housing so that there is no possibility of mixing up the pieces. The treads and housings can be marked as No. I left, No. I right, No.2left, No.2 right and so on.

Assembly of the staircase

When you have cut the housings and numbered them the strings and treads can now be fitted together as a unit. You may need some assistance to do this, because of the weight of the strings. You will also need two low stools or saw horses and some sash cramps. Lay one string on the stools or saw horses with the face with the housings uppermost. Position the treads in the housings as numbered. Lay the other string on top of the tread ends with the housings downwards. Align the treads with their housings, then apply glue to the upper ends of the treads. Knock the upper string onto the tread ends. Cramp the assembly. When the adhesive has dried, turn the assembly over and knock the other string off the treads. Apply adhesive to the ends and knock the string back down onto the treads. Then cramp the assembly up again. The next step is to screw the treads to the strings.

To achieve a good finish you can either use brass screws and cups or you can use ordinary steel screws counterbored below the surface of the strings. The cylindrical gap between the screw head and the surface of the string can be filled with plugs cut with a plug cutter. These are glued and tapped into the. countersunk holes and arranged so that the grain matches that on the string. Any part of the plugs that protrudes can be cleaned off with a smoothing plane when the glue is dry. Once the assembly is complete, the strings can be cut to the size required. At the top, the strings are fixed to a timber trimmer-a piece of wood slightly heavier than the floor joists, and which will normally be in place already on the upper floor.

The angled end of the top of the strings butts against the side of the trimmer and. is screwed in position. At their bottom end, the strings should be left a little over length for the time being. At the bottom, the strings are fixed to newel posts. There are several methods of fixing these to each other and of fixing the newel post to the floor. In the first, the strings are double mortised into the newel post and a timber dowel pushed through the tenon and the newel post. In the case of a timber floor the newel post can be set into the floorboards so that its bottom end rests on the concrete underlayer of the floor. There should be a damp course between post and concrete.

The second method involves the same joint between the strings and the newel post, but the newel post is fixed to the floor by means of a mild steel dowel. This method is only suitable if the floor is concrete. In the third method, the strings and handrail are housed into the newel post. These are then screwed together. In this construction, the newel post ends at floor level but the strings are inset below the floorboards with their ends butting a floor joist, or a specially inserted timber block between the joists if these run the wrong way.

Supporting treads with spines

This construction method involves supporting the treads from underneath by means of spines. The setting out of the spines was described earlier. The treads, in this type of design, are supported by triangular wooden blocks whose size depends on the going and rise of the treads. Their shape is similar to the triangular template cut earlier. The blocks are housed in a l3mm x l3mm groove cut along the centre of the top edge of the spines. Cut a tongue on the bottom side of each block (the wastage caused by this means that the blocks will have to be cut out slightly larger than your template).

Glue the blocks into the groove so that their top edges are in line with the stepped-off pencil marks made earlier with the template. Screw the treads to the blocks with brass screws and cups, or fix them with timber dowels. The fixing of this design of staircase to the floor and trimmer is the same as that for a staircase constructed with strings, except that the spines are not attached to a newel post.